The Case For Neuroplastic Pain

Getting certified in Pain Reprocessing Therapy (PRT) is the latest step I’ve taken to support my client community.

PRT is a system of psychological techniques that retrains the brain to respond appropriately to signals from the body, breaking the cycle of chronic pain.

I’m extremely excited to be digging deep into this new material with my clients, and to expand my practice to include this cutting-edge, research-validated treatment for chronic pain.

What’s more, PRT offers my practice a very tangible, research-backed structure that wraps around much of what I've learned and intuited through 14+ years of working with clients challenged by often-complex and confusing chronic pain symptoms.

Let's start out here by talking a bit about what exactly pain is.

Pain, at its core, is a danger signal generated by the brain. It is not, as we often believe, indicative of damage or injury itself. You can think of pain as your internal alarm system; a neurological signal generated to protect you from danger and harm.

If you accidently lean against a hot stove, for example, you want that pain signal to quickly and efficiently yell at you so you don't do significant damage to yourself, right? It's highly functional. Similarly, if you break your leg it’ll be remarkably painful, effectively keeping you from walking on that leg so you don’t damage it further.

In these instances, pain is (perhaps a bit paradoxically) a very good thing, right? It’s keeping you safe from danger.

Those examples aren’t reflective of all pain, however, especially chronic pain. So it’s important to understand that there are different types of pain. We can break them down generally into two camps:

Structural Pain: Pain that is directly-connected to a bodily injury or abnormality. Think about the pain when you've broken a bone or sprained your ankle. Structural pain is normal and healthy in acute injury situations, like the examples I mentioned above.

Neuroplastic Pain: Pain that’s caused when the brain misinterprets safe signals from the body as if they're dangerous. With neuroplastic pain you can think of that internal alarm system as being stuck on “on,” very often by mistake. This type of pain is remarkably common in chronic pain situations, and is very often a factor even when there’s clear evidence that long-term pain situations are connected to structural factors. Working with neuroplastic pain is the focus of PRT.

Structural pain is in many ways very straightforward — you’ve injured something and your body’s telling you it’s dangerous if you use it.

Neuroplastic pain can be a trickier to wrap our heads around though since, by definition, it’s pain that we’ve learned to be in (“neuro” refers to the nerve cells in your brain & body; “plastic” to the ability to sculp, mold, or modify — it’s a term commonly used to describe our ability to learn).

So, if you’re suffering from chronic pain, how can you begin to parse apart whether you’re dealing with structural pain (pain related to an actual physical injury) or the more-commonly encountered neuroplastic pain (pain your brain has learned to be in)? Especially if you’ve received a diagnosis or imaging results that prove there’s something wrong with your body?

To figure that out, it makes sense to break down the data around the correlation between having positive imaging results or a diagnosis and your likelihood of being in chronic pain.

Recent research tells a pretty remarkable tale about the prevalence of structural injury or abnormality and its connection to pain symptoms. As one powerful example, check out this data on the frequency of structural abnormality in populations with no pain symptoms from a study published in the American Journal of Neuroradiology:

I mean, seriously, look at those numbers!!

The data above is important to get y'all -- if you're 40 years old and have ZERO pain, you have a 50% chance of having a bulging disk. If you're 50, 60%. Those numbers get even higher as the decades pass, and this is an example of just one type of structural issue.

The flip side of all that, naturally, is that if you're a 40-year old that's experiencing pain, you have a 50% chance (or 40% chance for a 50-year old) of having zero evidence of a bulging disk.

The implications here are massive. What this data means is that, effectively, there’s very little connection between structural injury or abnormality and chronic pain.

These conditions are often referred to as “normal abnormalities” — normal signs of aging and wear in a human body. Having normal structural wear in your body does not mean you’ll be in pain. Period.

Many chronic pain patients have been unable to get a clear diagnosis or results from imaging that “prove” there’s something wrong with their bodies. This is why.

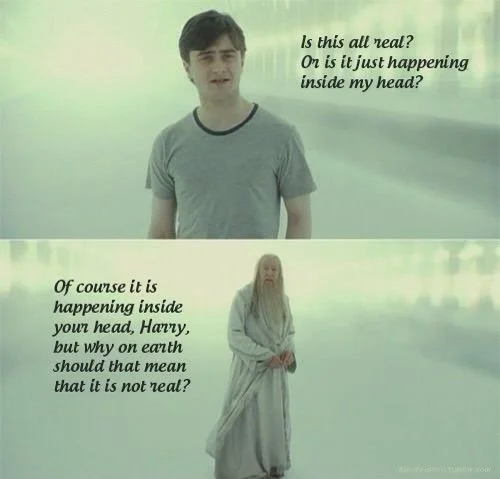

That information alone can be a mind-blower. And one of the first & easiest places to go when considering the possibility that your chronic pain doesn’t come from a structural problem is along the lines of, "so is this all in my head?" (or, more strongly, "I'm not just making this up!")

It's critically important to immediately check any thoughts like that at the door.

Your pain is very real, it just may be caused by your brain misinterpreting the signals it’s receiving — neuroplastic pain — creating chronic pain when it shouldn’t be.

One of the biggest challenges with chronic pain is that our brains f___ with us.

Often, and especially when we're stressed and on alert (for any reason), our brains can fire off pain signals. There's a biological overlap in our brains between the different systems that assess for threats. So, we may be stressed or in psychological danger, and our brains can misinterpret the situation for physical danger.

Result? We develop pain.

Australian neuroscientist Lorimer Moseley put this dynamic succinctly (and entertainingly) in his Ted talk -- "It's not something that comes from the tissues of your body; there's nothing there...100% of the time pain is a construct of the brain."

We know now that pain is constructed in your brain, through no fault of your own. And all pain is real pain.

What’s ultimately happening with neuroplastic pain is that your brain is uncertain if things are safe, and so it’s firing off pain signals in order to ensure that you don’t do anything rash, that you do everything you can to stay safe.

The solution then is to relearn how to perceive the sensations you’re experiencing in your body as safe. To teach your brain that the sensations you’re experiencing are simply sensations, and that there’s no actual threat to your body that needs to be met with pain signals to keep you safe.

And the upside here is that treating neuroplastic pain is much simpler than undergoing something invasive like orthopedic surgery.

So, is your pain neuroplastic?

Here are some of the clues you can use to help you understand a bit more about your pain, and if there’s potential for it to be neuroplastic instead of structural:

Your pain originated during a stressful time, or without specific injury.

Your pain has persisted beyond the normal course of healing (typically 3-6 months) for a specific injury.

Your pain is inconsistent — sometimes an activity hurts & sometimes it doesn’t (structural pain, like when you’ve broken a leg, typically hurts every time you use your body in a particular way).

You have multiple, unrelated symptoms — like a combination of leg pain, lower back pain, and neck or shoulder pain.

Your pain is triggered by stress, and/or it decreases when you’re engaged in something enjoyable.

You have a tendency toward certain personality traits, like self-criticism, anxiousness, perfectionism, and even conscientiousness. These traits have a tendency to regularly put people into a state of alert, which can increase the odds of developing neuroplastic pain.

There’s a lack of a physical diagnosis, or your doctors are unable to find an apparent cause (the important caveat here: remember the table above showing that research data proves that a diagnosis doesn't always equate to a reason for your pain!).

So, if you think your pain may be neuroplastic, but just aren’t sure (or if it’s a bit uncomfortable or “out there” for you to consider), I’d encourage you to try this experiment:

Start by simply taking notice of the times when your pain is worse, and the times it's better....what's happening in those moments?

Write it down, start collecting evidence for yourself so you can see the ways your pain changes depending on your activities or mood, and have something to lean back into when you’re dismayed or stressed by your pain.

There may not be anything complex or "wrong" with your body. There may be a simpler solution for you. You may just need to retrain your brain to feel & experience greater safety around the symptoms you have.